Interviews with Uncle Rudy

Date: 2018

Transcript for Mono_005

Rudy:

All right.

Tina:

So, David, do you have questions?

David:

Yeah. So maybe we can start by, what would you want your family to know about you?

Rudy:

Let me get my thoughts together. I would just want them to know that I tried to live a good life. I wasn't always there for my two daughters. Well, I tried the best I know how. I love sports. I would go and look at a ball game, if it was 40 miles away. If it was my team playing, I... You have to excuse me. It's not coming out the way I want it to come. Hey, look, I'm honest. I know what I want to say, but I don't want to gather everything where you don't understand where I'm coming from. You understand?

Tina:

Yeah, I understand.

Rudy:

But I just love to do things to make people happy. I wasn't the kind of a person that would go up and try to bully people, or know it all. I just wanted things to be right. And I know you can't be right all the time living in this world. But I had a beautiful family. I grew up with my aunts and uncles, and my grandmother and my grandfather, which you guys don't know. And when I grew up, when my aunts... I went to school with them, even though I wasn't in school. When they ate lunch, grandma fixed lunch for me also. I would meet them—we lived on Roberts Avenue, and my Aunt Doris, my Aunt Cavelia, and my Uncle Judy, which they call him Hat, everybody knows him as Hat. And when they would come home for lunch, my grandmother would say, "Sit down, you can eat too." I'd said, "Grandma, I just ate breakfast." "That's all right. Sit down there and eat anyway."

We just had a lovely time together growing up with my aunts, because it was only two of us, my brother next to me, and me. And I know a lot about grandma and grandpa that I can tell you, that really made me happy. My grandfather had an old car we called the LaSalle, and the only reason was it wouldn't start in the driveway. My uncle and I would have... I would help push. I wasn't doing nothing because I was too small, but Junie did. We'd call him Junie, he did most of the pushing. We pushed it out the driveway on the hill, and pushed it down, and made sure it drifted down the hill. During that time, there wasn't no automatic. It had a clutch. So in order to start, you had to let out on the clutch and it would jerk, and then it would start.

If it didn't start, we would've had to push it back up the hill, Junie and I... well my uncle, because I wasn't doing nothing because I was so small, and then my grandfather would get out on the side and push on the side on the driver's side. And they would get it up to a certain distance where it would drift and start. And then he would get in there and then it would kick over. And when it'd kick over, he would give me a nickel. Junie wouldn't get nothing. And I kept my nickels because the ice cream man came around every day. And when it's time to get ice cream, I had my money. Back during that time, you could get a Popsicle with 2 cents. There wasn't no 5 cents, 25 cents, 50 cents. I had enough money for a week that I made with my grandfather to get ice cream, and I didn't share it with my brother.

Tina:

Because you made that money, right?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

You made that money.

Rudy:

I made the money.

Tina:

It was your money.

Rudy:

I didn't give him nothing. I wasn't being stingy, I just wasn't giving him none of my popsicle. It was just good times growing up there. But anyway, my brother and I, we were the only ones living with my grandmother during that time. And my grandmother could make the best rice pudding in the world. And on Sunday mornings—Woo!—she would have little, I think it was small pork chops or whatever. It was something, a nice thick gravy and baked potatoes. Lord have mercy, you're talking about something good. I still taste them. And rolls would melt in your mouth. And they made rolls. Now look, they got all this electronic stuff and everything to poof, rise it and everything, for it to rise, they don't know what they used. But they would set it out, make it in the morning, and let it rise. It rolled out, dough would rise. Oh, they were the most tasty biscuits in the world. They wasn't biscuits, they were rolls. And I enjoyed that. I really did.

My grandmother, I mean could cook. I mean could cook. I remember I think my mother did the same thing right after us, because there were certain foods. Well, I was the one I didn't like fish. I never liked fish. I don't know why. But when my family had fish, I had baked beans and hotdogs. That was my thing. And you could say, till this day, I was raised on baked beans and hotdogs when they had fish. I mean I ate other foods, but baked beans and hot dogs were my thing. I loved every bit of it. And another thing, when my grandmother or grandfather, when I lived with them, I don't remember them... Well, maybe they did, but maybe they didn't, I wasn't the kind of person where they had to discipline y'all, "Do this. Stop doing this. Stop doing that." If I did, I don't remember it. I wasn't no goody goody, I'm pretty sure. But I just tried to be the best that I could coming up. I obeyed him.

My grandfather used to take me, we used to have a spare tire that was on the side of his car. I would try to ride on the spare tire. He said, "Nope, get your butt in this car." And that's what I did, I got in that car. And if you had seen that car, that thing was so long, old car called a LaSalle. I'll never forget that. It was green. It had a spare tire... No, it didn't. The spare tire was on the fender. And I don't know if you've ever seen them cars that have spare tires on the fender, that's what it was. And he kept that car a long time. I think he kept it until he got out the Army, because I don't remember when he was in the Army because I was young then. But he did serve time with them. Right now, if you want to visit his cemetery, he's buried down on Frederick Avenue, a place called—Taylor by Taylor Lane off Frederick Avenue, in a place called Paradise in Catonsville.

When you go down Frederick Avenue, like going towards the city, there's a little place called Paradise. It's called Veterans—it's a veterans' cemetery down there. And if you go up in that veterans' cemetery, grandma and granddad, granddaddy's grave, if you go, I can show the direction. You go in the gate, go to the top of the hill, make a left, then make another right, and another left. My granddaddy and grandma's burial is right there, the fourth tomb from the pavement. Fourth. And it would tell you William and Eva Burton. That's what his name and grandma's name: William and Eva Burton.

And times when I was growing up, I don't know what you guys remember, grandma was born I think, I believe it was in Oklahoma. She was part of the Indian tribe. Well, anyway, what I'm trying to get at, she had this bonnet that she always kept in her drawer, like a chief wear? Yeah, one like that. And sometimes, I would go in there and open that drawer, "Shut that drawer up. Shut it up." She would not let you touch that drawer. And that's a bonnet that she wore during the times that she was a youngin', you know? And I think I—did I mention that to you before?

Tina:

No, it's the first time.

Rudy:

I never mentioned that?

Tina:

No.

Rudy:

I thought I did.

Tina:

Yeah.

Rudy:

She told me, "Stay away from that drawer," and she wore that. Grandma's hair was long, come all the way down past her butt.

Tina:

Yeah, I remember her hair.

Rudy:

Cavelia's hair was very long. Oh, your mom's hair.

Tina:

Yes. I'll show you the picture. It was gorgeous.

Rudy:

Well anyway, growing up with my two aunts, Doris and Cavelia, when they were going to school, that was my most—moments. And then after I got grown, we moved. My father was in the Navy. And once he got out of the Navy, that's when all of us started multiplying. And I didn't know where they were coming from. Yes indeed. But anyway, during that time, staying with my grandmother, it was really enjoyable. Very enjoyable.

Tina:

So our great-grandfather, what was he like? Because I have no, of course, recollection of grandma's husband.

Rudy:

Oh, granddaddy?

Tina:

Your granddaddy.

Rudy:

He was a brown skin. That's who my Aunt Doris took after. Doris was pretty. She was. She had black hair. I never forget—long, black hair also. Cavelia's was black, all of them though, but Doris' hair was beautiful. Then she had that beautiful complexion, too.

Tina:

Okay. So he was a dark man in complexion?

Rudy:

Dark brown in complexion, yes.

Tina:

What was he like? It sounds like he was-

Rudy:

That's Janice. Jennifer's and them's mother, Doris.

Tina:

Yes. Yes. What was your grandfather like, our great-grandfather, grandma's husband?

Rudy:

He was very nice to me.

Tina:

Yeah, he seemed like he was.

Rudy:

Yeah. He treated me very well. He would give me a nickel for my ice cream, I remember that. Whenever I pushed the car, tried to get it started, I would get a nickel. No. No. No. No. No, three cents. A nickel's too much during that days. And I kept those pennies. Like I said, I had money enough to get the ice cream when the ice cream man came around.

Tina:

What kind of work did he do? What kind—what did he do?

Rudy:

You know one thing, I do not know what kind of work... I can't remember what kind of work he did. All I know, he was in the Army.

Tina:

Yes. That's what we hear

Rudy:

Right. And if he worked, I don't know. In fact, I don't remember nobody working. During that time, they might have been doing it, and I was asleep, but I just don't remember what kind of work he did at all. But I know... Did you hear about what kind of work he did?

Tina:

No. I guess you could do so much right there in the--wherever you lived. You could have your own little business going. Like grandma made rolls. I know eventually she ironed. She was ironing for men in the neighborhood, people in the neighborhood.

Rudy:

Right. Yep. Yep, she was ironing clothes, and she used to iron for white people, too. White people would bring these baskets of clothes, and they would drop them off. It was just like taking them to a Chinese shop or something. Yes indeed.

Tina:

Exactly. I remember that. I remember that with grandma. But with our grandfather, I never knew. But I knew you asked him what he could have done something like that, right out of the home, a business.

Rudy:

He could have done something I didn't know about, like I said I was real small during that time, because I think I wasn't no more than about—I wasn't even in school, high school. And I have pictures where we used to run around. They took pictures where we used to run around the car. It was broken down. Well, it never did start. It always had to be pushed, as far as I know of.

Tina:

That's so funny.

Rudy:

And then he had, what you call a crank. And he used to go to the front of it and wind it up and get a... That was to build the push-up power. I don't know how many times he did it, but he would take that little crank out the trunk, wind that thing around. And I didn't count the times that he did it, but the time that he... I think he wound it till it got tight. And when it got tight, that's when me and Junie, we pushed it out of the driveway onto Roberts Avenue to go down the hill.

Tina:

The same kind of the power, same way you had to do like the Victrola. We were rolling that, we were turning that knob yesterday to generate the energy.

Rudy:

Right, there you go.

Tina:

The same principle, I guess.

Rudy:

That's what you need. That's what he had to do to start his car. I knew that. And...

Tina:

Amazing. Amazing. So many years ago.

Rudy:

That was so many years ago. I'm 81 now. I made quite a few. I thank the good Lord day in, that I can remember some of these things. Sometimes, I can remember some of these things like it was yesterday. And mostly was, when I used to meet Aunt Cavelia and Doris and Junie on that hill, you know where Morningstar Baptist church is on Roberts Avenue?

Tina:

Yeah.

Rudy:

Okay. That's where I used to meet them at. Then I would take hold of Cavelia's hand up and run and skip like I'm running. She would always tell me, "Slow down. Slow down." And back then, they had them long dresses during that time.

Tina:

Yeah. They were wearing them long.

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

They were wearing them below the-

Rudy:

Below the knees. They were long. I remember that. And Junie used to wear them knickerbockers.

Tina:

Knickerbockers, oh my gosh.

Rudy:

Yes.

Tina:

The ones with the little tie—you tie them...

Rudy:

Yeah, knickerbockers. That what Uncle Junie wear.

Tina:

Goodness gracious.

Rudy:

Oh, knickerbockers, that's what we used to call them.

Tina:

With the suspenders?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

Did they wear the suspenders?

Rudy:

I don't know if he had suspenders, but he had the lace around the bottom.

Tina:

Oh my goodness.

Rudy:

And the socks, the long socks. That's what he wore.

Tina:

That was the outfit.

Rudy:

Yep. Well I don't know if you've ever seen the cartoons on, was it Little Rascals or something like that?

Tina:

Yes, uh-huh.

Rudy:

They have knickerbockers or something.

Tina:

I know what you're talking about. I can see them in my head.

Rudy:

That's what he used to wear.

Tina:

Uh-huh. That's so funny. That's so many years ago. So many years ago.

Rudy:

Yes, indeed.

Tina:

But life was so simple. It was much simpler. It was just-

Rudy:

Oh man. It was.

Tina:

You had your own because Blacks weren't allowed to go beyond certain boundaries. Because you told me the time that you were in, was it high school in Banneker?

Rudy:

Banneker High School, yep.

Tina:

And you wanted to kind of go into another area to play football. You went to look into playing on another team or something, and they did not-

Rudy:

See, during the time I come up, during the time that Aunt Cavelia and Junie and all of them was coming up, and Doris, they only went to the 11th grade. Banneker High never went to the 12th. I forgot. I don't know what year they started the 12th grade, but you only went to the 11th grade, because there's only three Black high schools in Baltimore County.

Tina:

Now the high schools, did that also include Junior High?

Rudy:

Yes. Yeah. One school.

Tina:

Was it elementary all the way through?

Rudy:

All the way through.

Tina:

All the way through until... Okay.

Rudy:

I can remember my teachers from every grade, especially elementary, because I think some of those teachers were there when I went to school. I don't know about Cavelia and them's class. I don't remember the teachers. But then when I started, they were there. I understand they were there before I could, because when I started in... See, I was born in '37. Six, that would give you what? Oh, see, I didn't turn six until October 8th. Back then, you had to be in school in September. It was September. But I was five years old when I started school. I was five. I wouldn't be six. I wouldn't be six until October, but you understand? You had to be six to start. But I wasn't going to be six. When school started in September, I couldn't go. Well no, no. I went, but I was only five years old. I didn't turn six till October 8th.

Tina:

Yeah. They just let you go in, you only needed one more month.

Rudy:

They let me go. But they let us go during that time, same way with my brother. He was born 18th of October. Everybody else was born before that. And I think Wayne and Ronnie was born in December. So they had to wait till the following year.

Tina:

Okay. So how did y'all get to school?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

How did you get to school? Because grandma and our grandfather-

Rudy:

Oh school wasn't far from Roberts Avenue.

Tina:

You guys could walk?

Rudy:

We walked.

Tina:

You walk, okay.

Rudy:

We walked. I don't care what the weather was, hot, below, or 20 inches of snow, whatever it is. We never stayed out of school when it snowed. We went. It could be high as that ceiling. We went to school. But like I say, during that time, well even that time I went to school, and I'm pretty sure when your mom went and Aunt Doris and Juniie, they only had three Black high schools. In Baltimore County, in Catonsville, it was Banneker. And Towson, it was Carver. Now there might have been something before I started, and then Dundalk, it was Stiles Point. And I know during the time I was coming up, we had to compete against each other, because there wasn't no segregation. Everything was integrated. And I just thank the good Lord. I started with integration. No, segregation.

Tina:

Segregation.

Rudy:

Segregation, and wound up with integration. And remember a Black president?

Tina:

Yes.

Rudy:

Yep, that's during my time. But as I was telling you, we only had 11th grade. And my first grade teacher was named Miss Brooks. My second grade teacher was Miss Ferguson. My third grade teacher was Miss White. In fact, Miss White had two grades. She had a third and fourth grade. Then we had one teacher that had the fifth and sixth grade. What was her name? Towns, Miss Towns. I'll get 'em. Two grades, we had two grades together, third and fourth, and fifth and sixth. We had the same teacher. But we learned though.

Tina:

It sounds like you learned more than what we learned in our systems now.

Rudy:

We did. We learned. We learned, and I mean, it was a little crowded.

Tina:

I know. But they taught well.

Rudy:

We learned though. That's what we did.

Tina:

I remember you telling me some things of what you learned and how they taught, how you learned. And they seemed to make sure you guys didn't go to the next level until you learned your basic math.

Rudy:

Yeah. And they would fail you just like that. Yes, indeed. If you want to ask me questions about anything, I can try to give you what I know about it. Right now, I can't think right off. If you ask me something, I can think back and tell you about it. But I can't--right now, I can't think of any.

Tina:

Yeah, but you were well-educated and that was being segregated.

Rudy:

Even about the family. If you would ask me something, I'll let you know. Well, I did and I'll still let you know.

David:

Can you describe some of the classrooms that you were in, and what did they smell like?

Rudy:

I'm sorry, I can't hear you.

David:

Can you describe some of the classrooms that you were in? What did they smell? What did they look like?

Rudy:

Wait a minute.

David:

Some of the classrooms, like your elementary school, paint a picture of what they looked like. What were the desks like, the floor?

Rudy:

Well, the desks were, it was one at a desks, and the desks and the chairs were all made one. You ever see them?

Tina:

Yes, we know—we've seen those.

Rudy:

All made ones. All made one. It wasn't like it is right now. And the desks and the chairs were made one. Like they had bars or something, whatever, holding the chair and the desk together. You couldn't move the desk where you want to all round the room. That was stationary, and that was it. But anyway, then we had that little, where we'd keep our books and stuff underneath, right there underneath, our pencils and everything. And then you were assigned that desk. That's where you sat. Every day you came to school, that was your seat. You didn't change seats. If you would come in late and you didn't have a seat, you just didn't have a seat.

No, I take that back. You knew where your seat was. You knew where it was, and that's where you went to. There wasn't no changing those seats. Then we had a cloakroom where you'd keep your coat, where you take your cap and coat and then hang them up, put them on the same rack, same hook. That's the one you used. You were assigned to that. Nobody else could hang their coat on your hook. We had names on them. And so if anybody took your coat off, anything, and it wasn't theirs, you got the wrong coat.

Tina:

Did you all take your lunch to school?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

You took your lunch to school or you went home for lunch?

Rudy:

No. No, we came home for lunch. You either take your lunch to school and—or come home for lunch.

Tina:

Oh, you had a choice?

Rudy:

Right. And during that time, we had, well we had an hour for lunch during that time. I think they cut it back to a half hour, 45 minutes or something, or 15 minutes or something. But we had an hour for lunch.

Tina:

Did you go home? Did you go home to grandma's? You went to grandma's house?

Rudy:

Mm-hm. Back during that time, I was going to grandma's house, because that's where we lived. We lived with my grandmother for about, I don't know how long. I know we lived, when I was in the first and second grade. And then that's when I think my dad got out the Navy then, like I said, when everybody started multiplying. I ain't know where they was coming from. "Lord, I ain't had no baby sister yesterday."

Tina:

And then all of a sudden...

Rudy:

In fact, I didn't even know my mom was pregnant. So it was only two of us when we started out, me and Bucky, me and Charles. Naughty, which that was my sister, oldest to Joyce. She was the girl. Then she came, there was three of us. And then Wayne. After Wayne, I don't know, it would be Sharon and Doc. We call him Doc—Ronnie, Sharon and Ronnie. Anyway, Daryl is the baby.

Tina:

Yeah. I kind of remember when he was born.

Rudy:

Who?

Tina:

I remember when he was born. We remember. Aunt Geneva was in her 50s.

Rudy:

Yeah.

Tina:

She was...

Rudy:

I couldn't believe it.

Tina:

Well in age.

Rudy:

I couldn't believe it.

Tina:

I know. It was wonderful.

Rudy:

I said, in fact, I didn't even give it much thought during that time. All I know, because my mother and Sharon was pregnant at the same time, because Gerald and Daryl, I think one was born in December.

Tina:

I remember that day, though.

Rudy:

Yeah. Yes, indeed.

Tina:

Oh my goodness.

Rudy:

That was strange. I ain't kidding, it really was. I wanted to believe and I didn't want to believe it. Well, hey nothing much I could about it, just except, hey, another brother.

Tina:

Yeah. One thing I must say about our aunts, we have been hard workers. Hard workers, all of us. In fact, grandma and grandpa, all the way down, that has passed all the way down to our children, working hard.

Rudy:

I remember like I told you, when I was in school, high school, I used to catch a train over to Aunt May, and I worked with Cavelia, your mom, and Aunt May during the boarding house. Yes, I did. I used to go take a train over on weekends and come back. I used to catch it on Friday, and May would meet me at the train station, and then I would stay there. And I loved that job. I loved that job very well. I would get paid twice.

Tina:

Oh, see? Uncle Joe.

Rudy:

Uncle Joe.

Tina:

Uncle Joe will pay again.

Rudy:

When he'd take me back to the same thing?

Tina:

"Give me some more money."

Rudy:

He'd slip something in my pocket. And I felt a hand going in the pocket. Now I ain't looked till I got in the train. Yes, indeed.

Tina:

Now, one thing, that Joey—I remember you telling me, Rudy, that Uncle Joe used to sell suits. He used to sell suits to entertainers?

Rudy:

Yeah.

Tina:

He used to keep it in the back of his trunk?

Rudy:

He used to sell suits to the entertainers of Motown, most of the people in Motown, like Michael Jackson and all them kind, Lloyd Price, Temptations doing their thing. Temptations wasn't.... When I was coming up, there were Drifters.

Tina:

Platters?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

Was it the Platters?

Rudy:

Platters, yeah the Platters. See, I wasn't into music.

Tina:

Yeah. But I tell you, they dressed-

Rudy:

I was into sports.

Tina:

... they dressed back in that day.

Rudy:

Yeah, they did. They dressed. Yap.

Tina:

Yeah, they did.

Rudy:

And I used to call them Vaseline hair. They used to keep them, what do you call them?

Tina:

The Cook Co. What do they call it? It starts with a C.

David:

Conk.

Tina:

Conk.

Rudy:

Conk, yeah.

Tina:

Yeah, the Conk.

Rudy:

Oh, they used to lay that stuff back. I always thought it was axle grease, the car. I did.

Tina:

The car.

Rudy:

I thought it was axle grease. I didn't know. Then somebody kept telling, "Oh, it's Vaseline they put on there." I said, "Okay."

Tina:

Well see, you had all that good hair. You and your brothers, y'all had that nice fine hair. Y'all didn't have to do all that. But some of the other guys, not the Indian roots, but the African roots came out and the little beads, so they had to get that perm.

Rudy:

Right. Yeah. We used to have a nice grain of hair. I think we took after grandma.

Tina:

Y'all did. Everybody in your family.

Rudy:

Yeah, everybody.

Tina:

Now I look at Cheryl and Sharon, all you got some nice hair.

Rudy:

Even my daughters.

Tina:

Your daughters too. Yeah, and long, long pretty hair.

Rudy:

Yeah.

David:

What kind of sports were you into? How did you get involved in sports?

Rudy:

All right. I got into sports. Believe it or not, we had this... No wait, before that, when I was in high school. No—was it high school?... Let me think now. I'm not trying to dream it up. See, I used to live down the road. We had a down-the-road gang and an up-the-road gang. We used to participate against each other. Up the road played down the road. And we thought we had the best players down the road. They thought they had the best up. That's where I really got into it. So it just moved right on into high school, grade school. And my father played ball. One thing, he was a good ball player. And I used to follow him. We used to follow them where they played on their teams, out to Druid Hill Park.

Tina:

Okay. Yes.

Rudy:

Right. So we used to follow, because my father had 10 brothers, and about four sisters. And every last one of them played ball. They had a team, nothing but Randalls, I remember that coming up. And we had a cousin, and his mother was a Randall, and he played shortstop, name was Mose Griffin. And he played shortstop. And we had another guy who was a police officer. He lived in Baltimore City. He pitched. I think it was the only two that weren't Randalls. The rest of them were Randalls. And my family could play ball. You could ask anybody in Catonsville about the Randalls. We could play ball. I don't care what football, basketball, baseball, when one sport come in, we participate in another.

So anyway, getting back, well we had this basketball team at school. And you couldn't start playing until you got in the seventh grade. Once in the seventh grade, you could go out for the basketball team, before that. But you had to be in the seventh grade to go out to the basketball team. But we did have one guy in my class, was in the sixth grade. This coach used to come down, get him all the time. He was good. His name was Joe Lynch, and he was really good. And he used to come down, get him out of class to take him. And he was in sixth grade, and he played with the guys in high school. Yes, indeed.

But anyway, getting back the way I got started, I just graduated up. And you couldn't wait to get up there to go out for the ball team. Whatever we had, most of our thing was basketball and track. We didn't have no football team, and we couldn't play against the white schools during that time. We had to play among each other, the three Black schools I was telling you about.

Tina:

Yes.

Rudy:

And then we did play with a few teams in DC. We played against Fairmont Heights, we played against Dunbar. And there was another team, was it Armstrong? Is it there a High School called Armstrong?

Tina:

Yeah. There was a... Well, I know it as a vocational school, but I don't know. It might've been. I don't know. I do know-

Rudy:

But anyway, it was three schools from DC we played for. Then we played Robert Moton, that was in Carroll County. Harriet Tubman, which is in Howard County. Bel Aire, which is up in Havre de Grace, played against them. But no white schools. No white schools. Everything was Black. And I was the first... Back during the time, the American Legion, what you know right now is called Jackson and Johnson.

Tina:

Oh, okay. They changed their name.

Rudy:

When they first formed the American Legion, they formed a baseball team. We got a baseball, and I was the first Black player to play at Memorial Stadium, during my time coming up.

Tina:

I remembered a lot of talk about you, Rudy, and how you were just... Were you on your way almost to play pros or something?

Rudy:

Yeah.

Tina:

It was very, very close.

Rudy:

I was very close. Yep, I was very close.

Tina:

You were very good.

Rudy:

But the babies got in my way.

Tina:

Okay, the babies.

Rudy:

Yep. See, I wanted to be a lover too, and that didn't work. It didn't work. Yeah. But anyway, I was the first Black... I played shortstop. I was the first Black player. I played on the All-Star team, but I played on.

Tina:

I hear some stories

Rudy:

Played at Old Memorial Stadium on 33rd Street. You remember that?

Tina:

I don't remember it. I just remember-

Rudy:

Well, that was the old Oreole park. Before the Oreoles moved to Camden Yards, they played at Memorial Stadium on 33rd and I played there, and I was the first Black player...

Tina:

I remember hearing

Rudy:

... during that time.

Tina:

Yeah, I remember the stories.

Rudy:

And that was a thrill. I wish I had those pictures. I had my own cheering squad. My uncles and cousins came out there to cheer me on. My first time to bat, guy threw and hit me in the back of my back. He didn't do it on purpose, I just got hit. I went down the first base, I stole second. When I stole second, they thought I was the fastest person in Baltimore City.

Tina:

My goodness. I always thought it was football, but it was baseball you played?

Rudy:

Baseball.

Tina:

Not football? Okay.

Rudy:

My only memory in football was we had this Catholic high school called St. Mark's. And it was down by Winter's Lane just before you get to Frederick Avenue, they had this field, St. Mark's High School. It was a Catholic school, all white. There wasn't no Black going there during that time. So I used to go down there and watch them practice when I used to get out of school. And this guy, preacher's name was Father Ferrell. And he used to see me. And then the reason why we knew him was, well we had Bible school during the summer. And almost our whole school went to Bible school. We went to Bible school down there like it was going during the winter. That's how come the attendance was real good. We had the sisters that taught us.

But anyway, that's where I got started. But that's where I got familiar with Father Ferrell. So he had this football team. When he was practicing. I used to come down and watch the practice. I'll never forget, he gave me a helmet. I was sitting there watching. I used to come down every time they would practice. He gave me a helmet and told me, "Get in there and run the ball." I ain't had nothing. White boys had everything on, pads, shoulder pads. All I had was a helmet. I'll tell you, believe me, I got that ball, I went through that line like it was a piece of paper. He looked, and then he told me, "Come over." He put his arms around my shoulder, he said, "Good job." But I couldn't go no further than that because during that time, it wasn't integrated. So that's where I stopped.

Tina:

That's when you stopped. Okay.

Rudy:

Well, I could play football. I could play all the sports, but I just couldn't participate in competition among each other, us Blacks, because we played everything. We played on the street, Winter's Lane, pavements and everything. We ain't need no grass. And then we had little raggedy field in the back of our houses, which we had to make our own ball field. And you had rocks and everything in there, because there wasn't no designed diamond or nothing. So we played up the road, down the road. We played among each other. But that was my most thrilling moment, was Memorial Stadium and St. Mark's Church when I ran through those white boys.

Tina:

I remember in Catonsville at Aunt Doris's house taking a tub bath. When it was time to get ready for bed and we had to take our bath, I remember her filling the big tub up.

Rudy:

Yp, that's what you did. She heated up the water.

Tina:

Yeah, heated up on the stove, and then she would pour it in a huge tub.

Rudy:

Right, huge tub, and everybody got their chance.

Tina:

Yeah. So it just amazes me. And I still, to this day, remember Castile soap. That's the soap I use.

Rudy:

What was it?

Tina:

Castile.

Rudy:

Castile.

Tina:

I remember David talked about smells, I remember the smell of Castile soap, and that's what I still use. But I remember it on Doris's kitchen, taking that tub bath. So when you were little, did y'all have running water like that in your house or did you have-

Rudy:

No, we had to heat our water up in the tubs, and also we had to take our latrines out and take it down to the outhouse during that time, too.

Tina:

You didn't have a flushing toilet?

Rudy:

Nope. Nope, we didn't have no flushing toilet when I was coming up, long time. We had what you call an outhouse, and we used to take our chains or whatever it was, take it down there, then come back, wrench it out with water, take it back upstairs before we could have it at night. Came through all those, big difference.

Tina:

A big difference.

Rudy:

But I'll tell you what, it wasn't like we kept it on a schedule. We did everything, where it wasn't that... too much shame. If you had to go to the bathroom, you went to the bathroom.

Tina:

Did y'all use toilet paper?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

What'd you use for toilet paper?

Rudy:

We had toilet paper.

Tina:

Like we have now?

Rudy:

Yeah, we had toilet paper back during then.

Tina:

Okay. But with paper towels?

Rudy:

Huh?

Tina:

With paper towels, you wouldn't have to tear off. You used one cloth that everybody used. And even the public, they used a cloth to dry their hands. It wasn't individual?

Rudy:

Oh, you mean to wash their hands?

Tina:

Yeah.

Rudy:

Yeah. Yeah, right. No, I ain't talking about when you had to wipe yourself or something like that.

Tina:

Yeah, it was regular toilet tissue.

Rudy:

Regular toilet paper, right.

Tina:

Okay.

Rudy:

Yeah. Old days. I'll tell you, we came up there during that time. It wasn't easy.

Tina:

It wasn't easy.

Rudy:

Now you can imagine what our ancestors went through. Back during the time, I was in the '30s. It was a little better, but still, the memory's there.

Tina:

Right. Lord, it's amazing because it's like, what did they use before toilet paper? And there was a point when there wasn't any toilet paper off the roll. But you grew up in a time when toilet paper on the roll was there.

Rudy:

Right. During that time, things would gradually-

Tina:

Gradually change.

Rudy:

Yeah, changing.

Tina:

All right. David, you have anything else?

Rudy:

I remember when we had cars, street cars and everything, they would use one track. They had two hooks on them. They would use one hook to go forward. And when they were ready to come back, they would change it and put the other thing up and go backwards. This was going from Catonsville to Ellicott City, right?

Tina:

Right.

Rudy:

But we had what's called the 14 line, which is Everson Avenue, that went from Baltimore City, which was North Bend... No. What was it? North Bend? Yeah, North Bend in the city. That was a 14 line. That came all the way out to Catonsville. And then it would change to the 9 from Catonsville to Ellicott City. And that's where people in Howard County... See, they weren't integrated, they went to Harry Tubman in their school. I don't know where they went before that. But anyway, they came to graduate. They went to Howard County, and then there was a place called Oela. You ever heard of that?

Tina:

No.

Rudy:

That was in Baltimore County. They came down to Banneker.

Tina:

Okay.

Rudy:

It's Ms. Cheryl.

Tina:

Okay.

Rudy:

Yeah, Cheryl?

Cheryl:

Yes, sir, [inaudible 00:47:55].

Rudy:

Who? Yeah, go ahead, Cheryl.

Tina:

Tell Cheryl I said hi.

Rudy:

Huh?

Cheryl:

[Inaudible 00:48:03].

Rudy:

Yeah-

Transcript for Mono_003

Tina:

Thank you.

Rudy:

Thank you.

David:

Test.

Rudy:

Yeah. I'm thanking you. Look, some of the words or something might come out wrong. Just tell me.

Tina:

You just be yourself.

Rudy:

I'll just think back and I—see my baby daughter tell me. I say things I shouldn't say and then when I think about it, "I shouldn't have said that."

Tina:

It's all right.

Rudy:

Only when I'm forming an opinion or something like that, that's what happens. You understand?

Tina:

Uh-huh.

Rudy:

I'll come out and the reason why I do that, because I feel I might forget if I don't say it. So I just let it go. I just let it come right on out. So I try to be real as possible. I know I ain't perfect and I know this aged, old gray man like he used to be. But I just try to be as real and believe, make thing believe as much as possible. You know?

Tina:

Yes, yes.

Rudy:

Because I love living.

Tina:

I know you do.

Rudy:

I know we all do. Yes indeed.

Tina:

And because you have loved life for so long, that's why you are still with us and hopefully continue with us for many more years.

Rudy:

[inaudible 00:01:17]. Be loved by others.

Tina:

And then you have such a positive outlook on just life.

Rudy:

Well, I try to have a positive. I wake up every morning and I look out there and see that beautiful weather out there. You don't know.

Tina:

Yesterday was gorgeous.

Rudy:

Yesterday, but tomorrow is not promised to you. And I might get a little emotional every now and then, but hey, I just feel good.

Tina:

I know-

Rudy:

I really do.

Tina:

You know we cry-

Rudy:

I can't move around like I want you, but I just thank the Lord for letting me do whatever I can. You know?

Tina:

I think it'll be distortion. Yeah. Rudy, I'm going to turn this off a little bit so that we-

Rudy:

Go ahead.

Tina:

So we can won't hear it in the background.

Rudy:

All right. Go ahead

Tina:

And-

Rudy:

You can put it anywhere you want to. Pretend we in Hollywood.

Tina:

Yeah, we in Hollywood. We got to get-

Tina:

Thank you.

Rudy:

Thank you.

David:

Test.

Rudy:

Yeah. I'm thanking you. Look, some of the words or something might come out wrong. Just tell me.

Tina:

You just be yourself.

Rudy:

I'll just think back and I—see my baby daughter tell me. I say things I shouldn't say and then when I think about it, "I shouldn't have said that."

Tina:

It's all right.

Rudy:

Only when I'm forming an opinion or something like that, that's what happens. You understand?

Tina:

Uh-huh.

Rudy:

I'll come out and the reason why I do that, because I feel I might forget if I don't say it. So I just let it go. I just let it come right on out. So I try to be real as possible. I know I ain't perfect and I know this aged, old gray man like he used to be. But I just try to be as real and believe, make thing believe as much as possible. You know?

Tina:

Yes, yes.

Rudy:

Because I love living.

Tina:

I know you do.

Rudy:

I know we all do. Yes indeed.

Tina:

And because you have loved life for so long, that's why you are still with us and hopefully continue with us for many more years.

Rudy:

[inaudible 00:01:17]. Be loved by others.

Tina:

And then you have such a positive outlook on just life.

Rudy:

Well, I try to have a positive. I wake up every morning and I look out there and see that beautiful weather out there. You don't know.

Tina:

Yesterday was gorgeous.

Rudy:

Yesterday, but tomorrow is not promised to you. And I might get a little emotional every now and then, but hey, I just feel good.

Tina:

I know-

Rudy:

I really do.

Tina:

You know we cry-

Rudy:

I can't move around like I want you, but I just thank the Lord for letting me do whatever I can. You know?

Tina:

I think it'll be distortion. Yeah. Rudy, I'm going to turn this off a little bit so that we-

Rudy:

Go ahead.

Tina:

So we can won't hear it in the background.

Rudy:

All right. Go ahead

Tina:

And-

Rudy:

You can put it anywhere you want to. Pretend we in Hollywood.

Tina:

Yeah, we in Hollywood. We got to get-

Transcript for Mono_006

Tina:

Probably one more question that will, kind of, summarize everything, because we're hoping that our younger generation that's going to be listening, will kinda get a picture.

Rudy:

I hope I could inform you much as possible.

Tina:

You did a wonderful job. Thank you. You know--

Rudy:

I don't remember too much, but I remember coming up with my aunts and uncles. Especially with your mom, Cavelia and Doris, and Junie, and Grandma and Grandpa.

The car was amazing, trying to start it.

Tina:

But even though you had all those ... and I guess we would say, "Oh, I don't know if I could deal with all that. You know, going to an outhouse, taking a tub bath in the kitchen, cranking up the car."

Rudy:

Yeah. Cranking up the car, that's right.

Tina:

Our children now don't have to do that, but that was your life. And there was something very significant that it never changes now, that's missing, like the community, the love.

Rudy:

Love, right. Well, everybody knew each other growing up.

Tina:

Everybody knew each other--segregation wasn't all that bad.

Rudy:

Yeah. No, it wasn't all that bad.

Tina:

Exactly.

Rudy:

Because we know our place.

Tina:

There you go.

Rudy:

We knew how far we could go.

Tina:

And that builded community

Rudy:

You know, it didn't ... you know, to me. I mean, I know it was white and black thing coming up, but it just didn't dawn on me to say, "What? You couldn't go this." I knew that when I was ... I used to, this young man used to work with me, Wesley. His father used to work at a bakery down on Frederick Avenue. After school, we used to always go down there and help him wrap buns and bread, because he had a father that couldn't read or write, but he worked in his bakery and he used to ...

You know one thing? I didn't find out he couldn't read or write until late age. I was saying, we went down to bakery, this man was making--the stuff was already made up and then he went from there. Whatever it was, he probably worked there long enough. See, sometimes people are gifted. They don't need to know that. They could already--all you got to do is make it. The dough and everything's all made up and then you just make up the rolls and everything, just put them in the oven.

Well, we used to do that. Then we used to slice bread, too, because we used to train the blades and everything for sandwich bread. Different breads had a different inch of slice on it. Then we had buns and everything we had to wrap, pies and stuff. I used to bring me a lot of bakery stuff home. In fact, I used to put them in a pillowcase and bring them home.

Tina:

See?

Rudy:

Then, look. Look, the day afterwards. Oh, you talking about good.

Tina:

Nice and soft.

Rudy:

Shit, I used to fill a pillowcase full of buns and we had practice, we used to go up on the field and play ball. Boy, they couldn't wait till I got up there with those buns. We used to sit and eat them like it was a picnic.

Tina:

Oh my gosh. It sounds so good.

Rudy:

Yep, but it was nice. It really was nice.

Tina:

In spite of the prejudice and all that was going on around you.

Rudy:

Yep. All that was going on around us.

Tina:

You all just found comfort in each other, and joy.

Rudy:

Oh, another. I remember too, I was went down to ... I was really into sports. I went down to Catonsville Junior High and they had three ball teams. White, wasn't no Black. The Optimus, Rotary, Gowanus. It was three Black teams they had—four. It was four? Rotary, Optimus, Gowanus—I can't think of the other one.

Anyway, I used to go down there and watch them practice. I used to sit over there, because I wanted to go out for the team. While I was sitting there, this white guy came over and told me, he said, he asked me, he said "You know, you got program going on up in your community. What are you—" I remember him telling me that. I looked at him. He said, "Yeah," that means he told me that I wasn't invited.

Tina:

I remember, yeah, you telling me that.

Rudy:

He said, "Yeah, they have practice meetings up there, the whole ball team." That means I wasn't invited.

I just turned around, walked my butt right on back up Wnters Lane. As it is, the only thing that I remember during that time, because that was going there, I could beat all them guys playing ball. I know that. And this was before that I got on the American Legion team and I used to go there. This was the age of 12 and 13, something like that.

And this white guy came, he sure did, came over and told me. He said, "They have ball meetings up where you live at."

Now, I just thought about what he was telling me. I wasn't invited, but it didn't dawn on me during the time what he told me.

Tina:

Right, yes.

It seemed like it didn't matter because you had a lot to go back to. You had friends, you had family, you had a community, and you were okay with all of that.

Rudy:

Yeah, when he told me all of that, I just marched myself right on back.

Tina:

Right on back.

Rudy:

I had my own glove. I didn't need no glove, but I know I could play better than them white boys. I know that. Same way with football, when I went up when St. Marks was practicing. And Father Burrough told me, he gave me that helmet and told the guy to hand the ball off to me. I handed the ball on me, hit one guy on the line and kept on going.

Oh, I remember it just like yesterday. He said and Father Burrough, I saw him back there and he sat back there and left.

I don't know if they were scared to tackle me or what.

Tina:

Yeah. I heard you were not a small guy.

Rudy:

But anyway ... Huh?

Tina:

You weren't a small guy. Muscles and all that.

Rudy:

Yes, indeed, because what it is, I used to build my strength up. I used to work in this liquor store on Frederick Avenue. I used to pack beer and sodas and stuff and clean up. This was my job on weekends. I went down on Fridays after school and I went down on Saturdays and Sundays, Sunday mornings. I cleaned up this place and this guy paid me and I made good money. I don't know if it was back during that time, but I made more than $20, $30 that day.

Yes, I did. I sure did. I never would [forget], he had this other Black guy used to work for him. What he did—see, I worked for him for a little while along with this other guy. He used to lay money down on the floor. I used to come and clean up. When I come along, I picked the money up and gave it to him. It was right behind the register. I don't know if he was trying me or what, but I remember that.

I said, "Hey, Mr. Wicks," I said, "This was laying there on the floor." I just picked it up and gave it to him. Now, whether he tried him, the other boy, I don't know. I don't know what happened to him, but he wasn't there for, I know, after a certain time.

Tina:

Really?

Thank God you gave it back.

Rudy:

Yes, I did.

Tina:

That was just an honest man that you were.

Rudy:

But then I thought about it, say maybe he was trying me.

Tina:

Could have been.

Rudy:

But I gave it to him... it was a dollar. Most of the time it was a dollar bill laying around the register. I would pick it up and give it to him. "Mr. Wicks, this was laying on the floor."

Tina:

But David, do you have anything else?

Rudy:

I remember those things. I remember just ... huh?

Tina:

I was asking David, if you had one more final question before we end it up.

Rudy:

If you could think of anything, I'm trying to help you out.

Tina:

Thank you Rudy, so much. I think it's given us a really good picture in our mind that we can hold on to, how it was then and what it is now and how things might have changed, but the values and the love and the unity and all that kept our family and the community together.

Rudy:

Well, mostly I remember, I just—my grandmother, my grandfather. Your grandmother, grandfather, right?

Tina:

Yes.

Rudy:

They were so good to me, especially Granddad. When he used to give me them three cents for that ice cream or two cents or whatever it was. I had that ice cream money. Every day that man would ring that bell coming down there. I had my ice cream money and he would pay me, but he never give Junie anything. If he did, I ain't see him.

Tina:

Yeah. Little things like that. It's just a little gesture, but that's how you just—you remember that because that was a love for you.

Rudy:

I used to meet him. I'll tell you, like I said, I used to meet him right there on top of the hill in front of Morningstar Baptist Church. And I used to take hold of Cavelia's hand and I used to swing it, go march right on down to the house for lunch.

Grandma said, "Come on, sit down. You, might as well eat, too." I said, "Grandma, I just ate breakfast." "Eat. Sit down there and eat, boy."

Yes, indeed.

Tina:

I can see Grandma's apron and her handkerchief that she used to carry in her hand.

Rudy:

And look, could make things out of the blue. Didn't need no measuring cup.

Tina:

That's right.

Rudy:

Didn't no measuring spoon. I don't know if it was I was hungry, but anyway, it was good.

Tina:

Yeah. I remember the chicken on Sunday. Fried chicken on Sunday.

Rudy:

Fried chicken, yes.

Tina:

And those yeast rolls.

Rudy:

Them yeast rolls. That's right.

Tina:

Oh my goodness.

Rudy:

And rice pudding. Oh, my lord.

Tina:

I don't remember the rice pudding.

Rudy:

Yeah. You don't?

Tina:

No, I don't.

Rudy:

Well, I do.

Tina:

Oh, Joey might. Joey can, he's got some strong memory. Him and Kim and they used to be out with grandma's house too as they were coming up. But thank you so much Rudy.

Rudy:

I know when my mama passed, Joey got up there. He embarrassed me, but when he come up and said, "My mother used to take—I said. My mother told him, 'I used to take a can of baked beans and hide it underneath the table with it.

I said, "Man, I know Mama didn't—."

I just laughed.

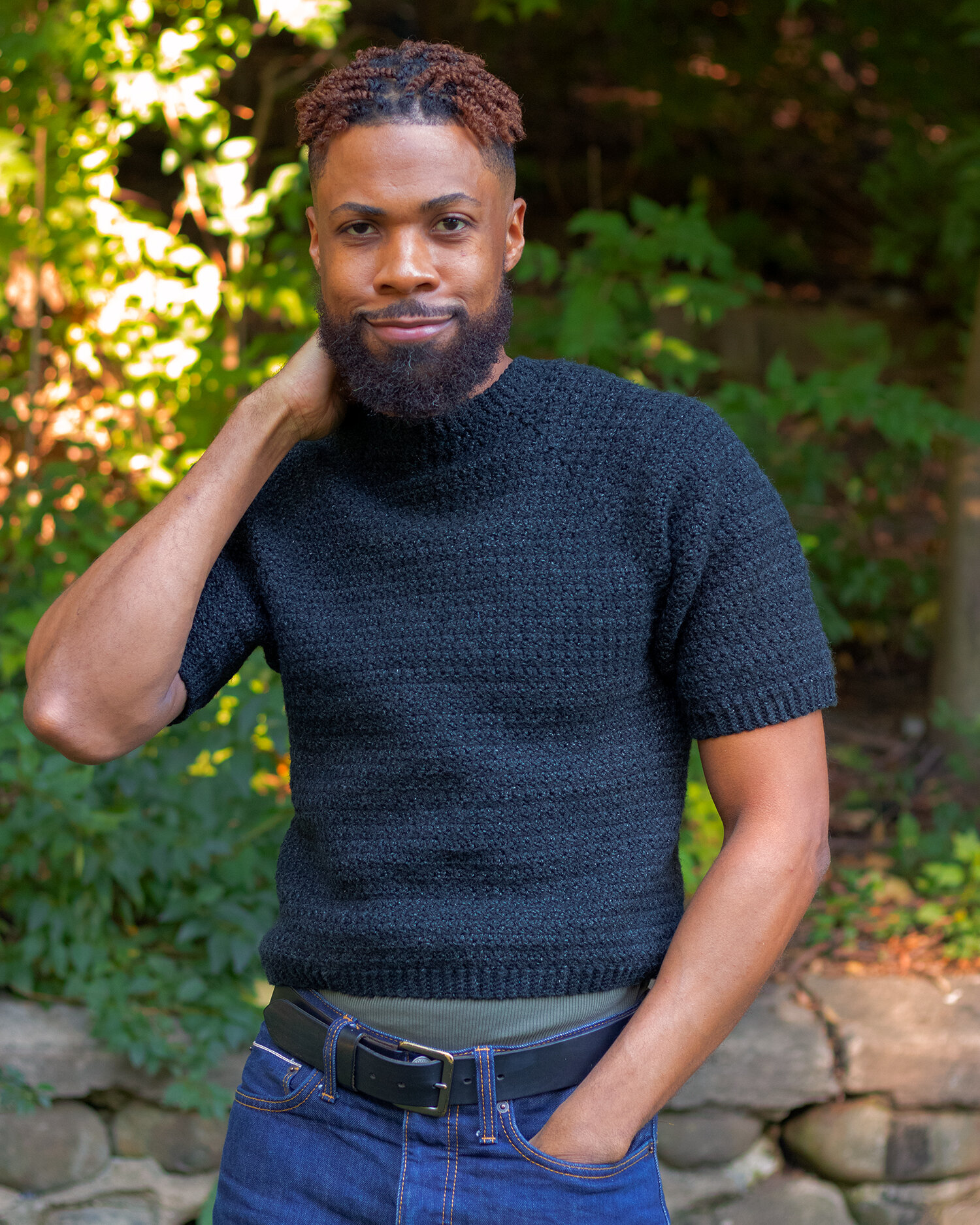

I learned how to crochet when I was 16 from a book. I quickly fell in love with the formation of stitches into something tangible—creations that were a direct result of my effort. There have been moments since then where I truly felt limitless with my creative potential as a crocheter. But in all of my twenties (a full decade), the joy of making warped into a pressure to be validated by others. I tried building a business out of my crochet passions and that desire stagnated my creative growth. I wanted to be “unique,” but failed to realize that my uniqueness needed the shaping and sharpening of other people’s knowledge and expertise, not just their applause. I wanted success and validation while in a gestation period, a time in my life where I needed to focus on learning, absorbing, and experiencing.

Like crochet, there is an art to living. Like crochet, I’m still learning how to widen my palette to receive and understand the invitations life offers me.

I’m grateful to have now experienced a level of professional success completely unrelated to crafting, which helped me to mentally decouple crochet with the possibility of revenue. Though that is, of course, achievable (and I applaud the people who have married craft passions with sustained income generation), I’m fully satisfied with where crochet sits with me in this period in my life. I’m going deeper into my love of crochet, exploring patterns for the first time, making garments for myself, and understanding that, like all crafts, there are varying levels of complexity to explore.

I feel curious about what I don’t know, and that curiosity feels delightful.